This post is part of a series of posts following the adventures of a man on a mission to explore 20 countries around Europe on a motorcycle – go to One for the road.

Chapter 2

I stop for a break at a petrol station, and stand beside the bike, sipping coffee and watching motorcycles and cars and lorries roar along the Czech highway. A dog barks in the field behind the trees, while above, very high cloud the colour of sour milk hides the sun. It’s muggy for April. The reality slowly surfaces, and at last I smile.

I am doing what I’ve wanted to do all my adult life.

Socks

The miles and hours of high white cloud have suddenly been swept away, leaving behind a glorious, sunny afternoon. It’s not quite sleeping-out weather yet, though, so after trundling round the pretty little town of Svitavy in a futile search for a cheap pension I book into a hotel just outside town: £30 for a double room, bathroom, TV, tea and coffee-making facilities, breakfast, air conditioning etc. The view is leftover snowdrifts in the car park and some trees that bring to mind the words ‘acid’ and ‘rain’. Still in a bit of a daze from the hours of noise and wind, I look out at it, thinking, Socks. Must wash the socks.

Oskar Schindler

Well, Oskar Schindler might’ve found Moravia pretty, but it hasn’t been what I would call outstanding, although it’s pretty if you’re from Norfolk or Belgium – indeed, positively mountainous if you come from Holland.

Svitavy was where Schindler grew up in the 1930s, before he went into Poland, where he chose the beautiful Krakow as a base in which to establish a business that would, commercially, go nowhere, but would save the lives of more than a thousand human beings, putting Krakow, the Holocaust and Ran Feinnes and Liam Neeson on the map forever. It was strange, last night, to stroll along the main street and picture the teenaged Oskar roaring up and down the cobbles on his motorcycle.

I think my left heel is beginning to rot. Not only are the holes in the sole getting deeper, but this morning, despite hot water and soap last night, I’m sure I smelt Feet.

Brno

Brno (confusingly pronounced ‘Brno’) is sprawling and ugly. The roads are bad and acid rain has killed or damaged most of the trees on the many hills that surround the city. There have been lots of hares and deer in the fields on both sides all morning, and I remember eight deer lying down in the middle of a huge field beside a German motorway yesterday morning.

Slovakia

Slovakia. On the motorway to Zilina, thousands of dead trees stand in deep water for miles. The road surface is still poor, but there’s a fast-emerging middle class in Czech and Slovakia – smart cars are everywhere.

Bratislava

Despite several circuits of Bratislava I can’t break into the centre, where my bed in The Gremlin hostel is waiting for me. Whole streets are being dug up, and others one way or for trams only. When I notice a group of gypsies lurking in a doorway staring at me as I go by for the fourth time, I know I’m not going to leave the bike unattended even while checking accommodation, never mind overnight. So I do the best thing to do in these circumstances: I give up.

Zilina

I point the front wheel at a sign that says, Zilina 189KM, and settle into the saddle for a three-hour ride. It stops raining, and I smile before nearly jumping out of my skin when a few hundred metres away a Boeing 737 roars up above the rooftops and immediately disappears into the cloud.

It begins to rain again.

Castles

The motorway road surface is excellent now, from which I watch as a number of great castles appear on hillsides to left and right, in this ancient landscape scattered, for some reason, with lots of huge signs, amidst some very evident poverty, inviting us to vote for Rowan Atkinson. Is Mr Bean coming to town?

That’s my man!

I stop for petrol, and then smoke a cigarette while stamping my feet and rubbing my hands together. The back door of a nearby parked car opens and a teenaged girl springs out. She’s pretty, very slim and heading straight for me.

“Hello!” she gushes.

“Hello,” I say, taking two steps backwards.

“You are okay?” she asks in a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed way.

“Er, yes, thank you.”

“You are looking for some place to stay?”

So that’s it. Young prostitute, sent across by her pimp to get trade.

“Well, I am, but I’ll be all right. Thank you.”

She is possessed of an energy that would light up a Christmas tree. She’s also very young, possibly no older than sixteen. She gestures towards the car. “My father would like to buy you a drink.”

Ha! Yeah, I bet he would.

“Your father?”

“Yes. Would you like to meet my father?” She’s wearing tight jeans and a thin, cheap windcheater over a tee-shirt beneath which there is very clearly no bra. Trainers. No make-up. Then the driver’s door of the car opens and a thick-set man of about 45 heaves himself out. Here we go. I drop the cigarette and stand on it as the man, unshaven and dressed in bulky, dark old clothing, approaches.

He speaks rapidly and brusquely to the girl, who answers while gesturing at me. He glares at me as he waits for the translation and my answer. I begin to feel annoyance rising in me, and reach for my crash helmet. Hear what she has to say and then move on.

“My father says that if you follow us to our hotel, he will buy you a beer.” Her English is very good indeed. All those German businessmen, I expect. Lots of practise.

“Your ‘hotel’, eh?” The ‘father’ is staring intently at me.

“Yes. My family is booked into a hotel not far from here.”

I almost sneer. “Your family, eh?”

“My father and mother and my baby brother.” And she points towards the car, where a middle-aged woman and a five-year old boy are smiling and waving through the windows.

Three hours later, I lie in bed in a roadside motel and wonder about Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. The gorgeous Jana spent the whole of supper translating for her parents and me as we chatted in the restaurant downstairs. Her father spent much of the time warning me of gypsies in all eastern European countries. When I asked why he’d invited me for supper, she replied, “Because my father hasn’t had a drink for three months.”

“Maybe I was waiting for a friend.”

“No, he knew you were alone. As soon as he saw you he told my mother, ‘That’s my man!’”

Skalite

Outside, the traffic swishes by on the wet road, while the lonely hills sleep on the horizon.

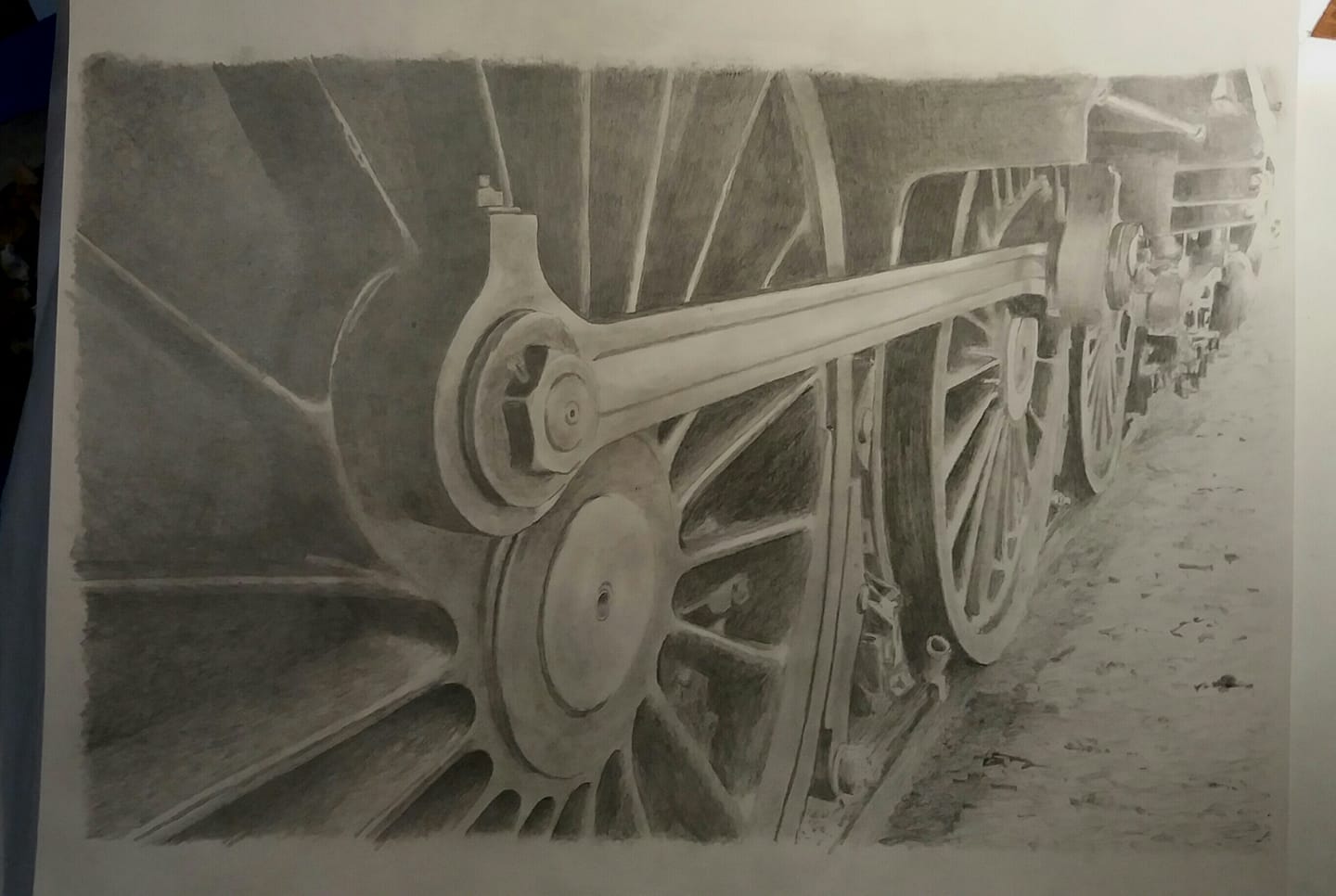

The clouds are more broken and fast-moving than they were yesterday, so there’s hope for a little sun today. I’ll turn right before the Czech border, to see if the railway at Skalite is the right one. The track heading north out of Zilina looked a bit mainline.

Snow and litter lie everywhere on the verges, strips and sheets of plastic hang or flap in the reeds, a fridge has been thrown down a slope; heavy rain which the sun tries to get through and my first stork gazes out from its enormous nest atop a telegraph pole. Four or five mongrels in a car park queue up to gang-bang a mongrel bitch wearing an expression recognisable as a look of ‘here we go again’ resignation.

Did the railway line branch off for Skalite? Or go north? It keeps coming and going across the road, which begins to climb, and it gets colder. Everywhere looks poor, with children waving sticks and streamers providing the first clue that this is Easter Sunday, along with crowds of people coming out of churches wearing their Sunday best. Very few cars in evidence, and snow is everywhere now. We go over the top, and occasional glimpses of the railway appear to the right, and then the road deteriorates badly and the railway line heads off into the forest on the left, and quite unexpectedly we come to the border crossing. It is absolutely brand new and totally deserted, a quite fantastic waste of money. Then we’re in among houses and cottages, separated by rickety old wooden fences, where chickens scratch and peck.

Country folk

The tarmac disappears and we’re onto cobbles. Here and there, folk are doing this and that, as country folk tend to, every single one of whom looks up at me as I go by – then I understand that the snows would have cut off these roads for the entire winter, for the last five months or so. I am possibly the first motorcycle to come through here this year.

Zywiec

I get lost in the small town of Zywiec (home of one of Poland’s most famous beers; a bit like getting lost in Guinness, Ireland, or Budweiser, USA), and I’m just sitting on the bike, examining the map, when a voice says, “May I help you?” I look up. A man in his twenties, dressed as if to play the part of a young Cambridge don in a BBC mini-series, is smiling at me through John Lenin spectacles.

I tell him what I’m looking for.

“It’s sixty kilometres – about forty of those English miles of yours.”

The railway line comes back, but the potholes are so bad my fingers become completely numb, with vibration white finger. We enter a small town, I see signs I’m looking for and follow them, turn right into a complex and stop. A young man comes up and begins to write a ticket. Beyond him I can see faceless windows, watchtowers and barbed wire fences. It’s not a parking ticket for a traffic violation I’m getting, it’s a parking ticket for a museum.

What the Germans would’ve called Koncentrazionlager 1.

What the rest of the world knows as Auschwitz.

Go to Chapter 3